The Will to Adorn: The Varied Expressions of Blackness

how do you define Black culture? Is it defineable?

“The will to adorn is the second most notable characteristic in Negro expression. Perhaps his idea of ornament does not attempt to meet conventional standards, but it satisfies the soul of its creator.” - Zora Neale Hurston from The Characteristics of Negro Expression

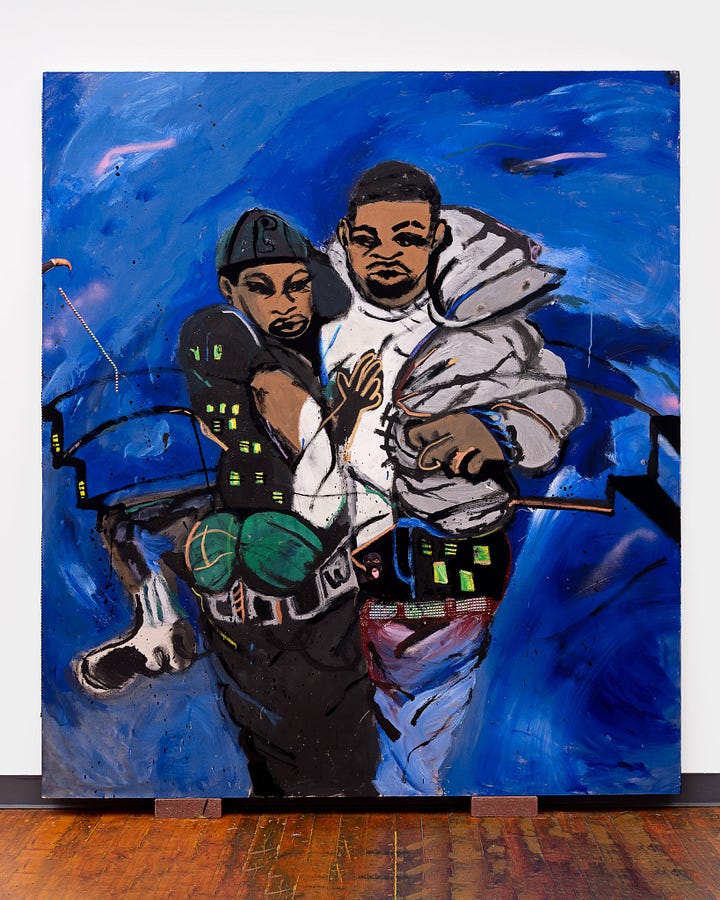

Black Star: Rebirth is Necessary by Jenn Nkiru, 2017

Last week, I watched an art history lecture produced by the Museum of African Diaspora (MoAD) and led by art historian and writer Jacqueline Francis, Ph.D. In the course, she cites the essay “The Characteristics of Negro Expression” by Zora Neale Hurston as a leading source in the documentation and breakdown of the building blocks of which Black culture is consisted of.

In Hurston’s study, she notes a myriad of aspects that define how Black folk show up in society as a culture, them being through the expression of: “drama, the will to adorn, dancing, negro folklore, culture heroes, originality, imitation, absence of the concept of privacy, and the jook.” While many of her notes resonate with my individual contemporary experience as a Black woman, her philosophy of Black people’s “will to adorn” was a particular interest of mine.

“GOD CREATED BLACK PEOPLE AND BLACK PEOPLE CREATED STYLE”

- George C. Wolfe

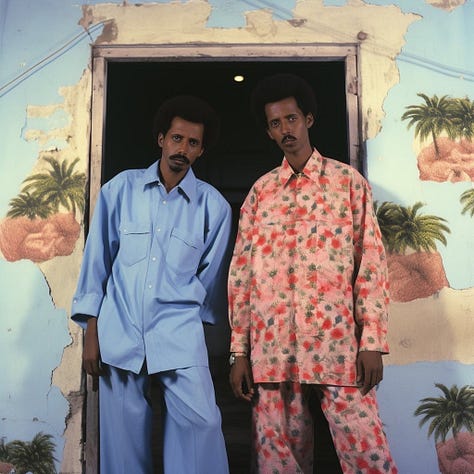

The presence of our “will to adorn” is so apparent within Black culture— across the Diaspora. It is present in the way we style our hair, the way we clothe ourselves, the way we furnish our homes; it’s in our vernacular. Recently, I’ve been curious to understand how we define Black “culture” in a digital age that de-emphasizes permanence and social exclusivity. With social media and the rapid expansion of the technology, we have access to infinite imagery and context at our finger tips. But what I’ve seen as Black “culture” portrayed via external media (music, visual arts, fashion & style, dance, etc.) has been a series of two dimensional and redundant visual aesthetics. What Black “culture” is imagined or understood to be has been translated through a repetition of images that often share motifs but not the cultural context which they’ve erupted from.

Before I go on a tangent, let’s dial back. How do we define “culture”?

culture - (from the Latin root colere) to inhabit, to nurture, to cultivate.

Historically, culture focused on the care and cultivation of deep-set values & ideas and property (cattle + crops) within a particular time, place, and society. Through a more contemporary lens, culture, especially Black American culture, is emphasized through our cultural property (music, fashion & style, dance, literature, etc.) (Francis, Ph.D.)

~

If we reflect on advancements made within the Black community as it pertains to culture, the most significant growth is visually seen through the capacity of our cultural property. This is not to say that the cultivation of Black values and ideas is not happening, but the rampant presence of systemic racism and the rise of the digital age have discouraged and stifled the passage of the historical context of cultural property through generations. Also, the mass censorship of African and Black history within educational institutions is an additional stressor that prompts younger generations to cling to the most familiar narratives of Blackness.

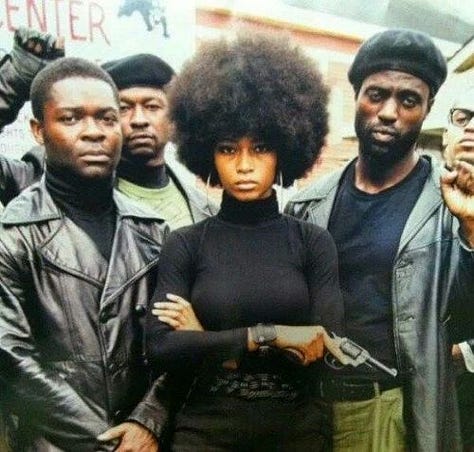

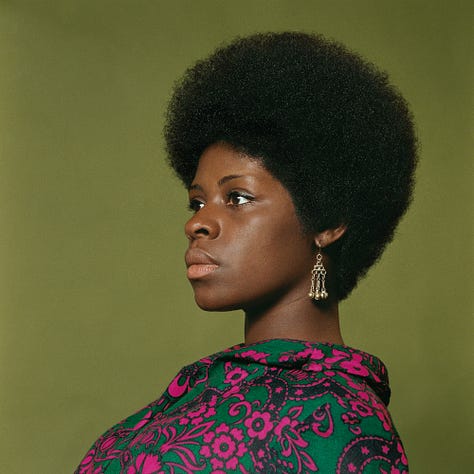

While scrolling on Pinterest or TikTok, I’ve come across the phrase “Black culture aesthetic” too many times to count. And I always ask, “what do you even mean by that??” The imagery is often images of either 80 - 90’s Black fashion and style: the gold bamboo earrings, grills, extravagant nails and hair or imagery from the Black Power Movement: afros, fists up, all black militant wear— all of which are absolutely Black, but do not encompass the variety of Black expression and adornment. My problem doesn’t lie in the imagery itself, but instead, the lack of variety within them, which presents a false narrative that Blackness is a monolith, and it’s not.

While I can acknowledge that the Black American style in the 80s & 90s was iconic, there are various eras and aspects of Black adornment that we can pull from to champion our culture. These Black renaissance movements like: the Black Power Movement, Black 90’s pop culture, the Harlem Renaissance, the Black Arts Movement, etc. were pivotal in amplifying the voices of Black people because they reflected the variance in Black thought, lifestyle, and expression — creatively and unapologetically.

A few weeks ago, I learned about indigenous West African tribes who are heavily expressive through their dress— whether it be through their jewelry, headwear, the colors of their clothing, hair styles, scarification, tattoos, etc. Many of these tribes, though, don’t have a written language and communicated with community through voice and the use of symbols— often exhibited on their bodies. This will to adorn, this will wear ourselves outwardly to hold and transfer a story, has been passed down through generations. This use of symbolism cannot be transcribed, but only inately understood through relatability. This makes me think of something James Baldwin wrote.

In James Baldwin’s essay, “ Of the Sorrow Songs: The Cross Redemption”, he explains how it is essential that jazz, a Black liberative expression during Jim Crow, be in a language that cannot be “decoded”; that it must abide by a beat that could not be understood by the outside influences. If it can be decoded or transcribed, then it can be censored, modified, and extracted. Symbols, metaphors, and motifs used throughout Black cultural property have stood as an internal code to steward Blackness and express our humanity without the interjection of the white gaze.

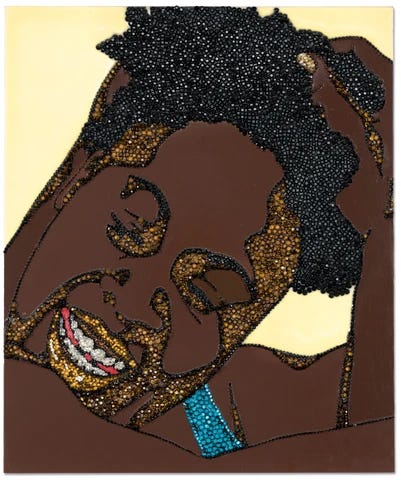

I feel this history was lost in the transition to the digital age where we intake most of our information from visuals that often only tell a glimpse of the story. And while these artworks I’ve placed through this essay do the same, by diversifying the lens of Blackness, we can learn to understand ourselves more broadly and all-encompassing. And maybe be more intentional in the ways we share our cultural property with others.

Define Beauty : Process by Rhea Dillon, 2018

welcome 2 my brain.